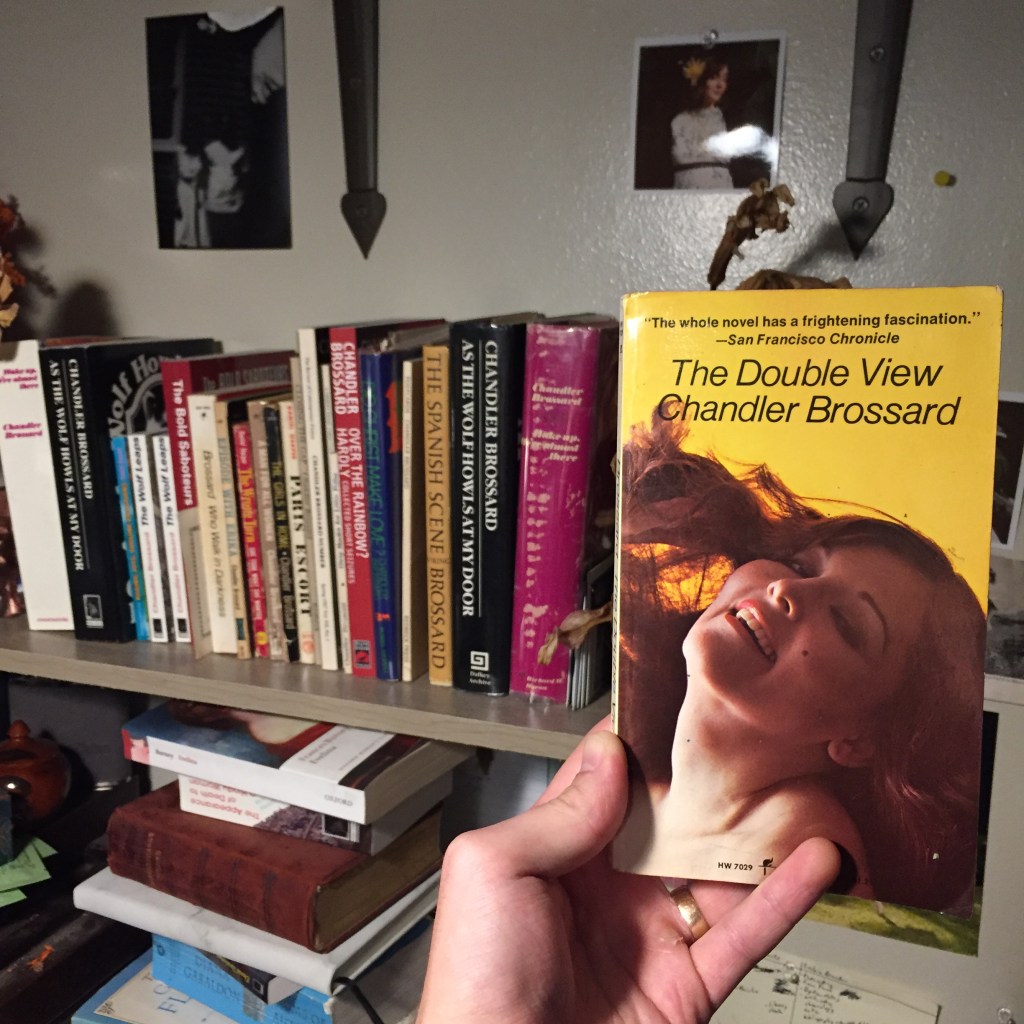

introduce with Brossard’s original title: The Double Dealers

Zen and the Art of Buggery

by Zachary Tanner

“I’m not sure that it’s even fair to ask you to write a foreward, introduction, or whatever, because I would not want to put what I experience with Brossard into words, you know, uh (long drag of a cigarette), be like (sip of coffee), like fucking someone who’s telling you as you’re going along what you’re feeling and why.”

-Rick Harsch

It is no coincidence that I share a first name with the bearded Zen master of Wake Up. We’re Almost There, as you are he, as you are me, and we are Chandler all together, constantly falling into and out of the abyss of one another’s “eternal and fathomless” human consciousness. Zachary (I, you, he, she, we, they) reminds his pupils “the mind flows out as it naturally enters into contact with any environment” and we’ve all been ruined by “Aristotelian logic…Everybody except April.” Who’s April? The most notorious vixen since Juliette for one, but, more pertinently, a single player in a bizarre troupe of Everymen conspiring over 500-some-odd pages in the grand delusion of staging reality by the magic of sensual clairvoyance and osmotic kinesics. As the novelist-within-the-novel George says “I am someone else, or several people as we go on, and boy do we go on.”

Next year will mark 50 years since the first hardcover edition of Wake Up (Richard W. Baron, 1971) and 49 years since the last paperback edition (Harrow, 1972). You may wonder: why have I never read this book? Why did it take the Great Anti-American Novel a half-century to be repatriated by an infinitesimal nonprofit press in Slovenia?

Part of it is retaliatory suppression by a gatekeeper from the New School.1 In April, 1971, Anatole Broyard, Brossard’s former friend and lifelong literary nemesis, published an obscene review of Wake Up in The New York Times titled “A truly bad book just doesn’t happen.”2 The review opens “Here’s a book so transcendently bad it makes us fear not only for the condition of the novel in this country, but for the country itself.” What a preposterous sentiment! Surely by 1971 any decent American citizen was beyond zeitgeist crisis and had personalized the horror, wondering: how-the-fuck-do-I-get-out-of-this-filthy-wasteland? The prudish review complains of the novel as “sexual circus,” of its “revolutionary rhetoric,” and “well over 500 pages of copulation, cunnilingus, and fellatio.” Call me pervy, but I’ve never read a negative review that buttered me up quite like this one. Have I been desensitized by too many dirty French books with talking cunts and naughty frontispieces? Perhaps. Later, Broyard is also quite humorously baffled by the “indiscriminate couplings” of Brossard’s prosody and gives four examples of befuddling language some of us would call poetry, the set of which Steven Moore later reclaimed as synesthetic Zen koans.3 The coup de grâce is in the penultimate paragraph when Broyard invalidates not only himself but the entire ass-wipe publication in dismissively lumping Wake Up together with Joyce, Céline, Genet, Henry Miller, Günter Grass, Thomas Pynchon, and John Barth. A stacked roster, to be sure. Surely anybody whose home library contained even worn paperbacks of these works would be a fast friend of mine, but more likely a reader who has heard of any of these authors has a few HCDJs from each. How unfortunate that even in 2020 such dreamboat intellectuals are less common than flat-earthers. What is more, Broyard fails to note the Marquis de Sade (who is mentioned more than once in the text) or Marguerite Young, their Greenwich Village contemporary whose landmark Miss MacIntosh, My Darling (Scribner’s, 1965) is equally dense, phantasmagoric, and forgotten. Two years after Wake Up, when Brossard published his manifesto distinguishing “literature” from “fabulous fiction,” a public indictment against the rampant fraudulence of the mod-lit scene, he aligns himself no less with Homer, Hugo, Melville, Proust, Queneau, Jünger, Kafka, and Musil, among others.4 It also calls to my mind Nabokov’s transgressive masterpiece Ada, or Ardor: A Family Chronicle (McGraw Hill, 1969), or the 8mm mud shark pornos and monster dicks of The Mothers’ Fillmore East – June 1971, though it seems unlikely Broyard would have been loose enough to enjoy either of those. Nor could he have known that the Nazi orgies in this transcendent doorstopper predate those in the National Book Award-winning Gravity’s Rainbow (Viking, 1973) by two years and the complex sociological motion of McElroy’s Women and Men (Knopf, 1987) by sixteen. Sadly, not everyone shares Brossard’s (and my) contempt for conventionality, and the review virtually banished the dear author to the Borgesian labyrinth of little presses.

Finally, it is coming back across the Atlantic in photocopy paperback of the first edition in all its sic glory, as if via wormhole from an alternate, utopian reality without copy editors or record company tycoons in which the Grateful Dead were actually able to title their second live double album Skull-fuck.5

But Wake Up is more than the masterpiece that the counterculture forgot. What better time than now to bathe in its “indifference to difference.” Here’s a book for anyone with a respectable amount of self-contempt. It is a tool, like the I Ching or a tarot deck, to free your mind from “the shit of the bourgeois world.” It is an escape from the cultural diarrhea of the “Zonk box” in which the reader-participant is welcomed on equal footing as an intellectual and a compassionate human being. Dream with me, Brossard screams through his characters, and together we can subvert society for its lack of love. Rim jobs can save the western world! Leave behind this “Cannibalistic inhuman culture where the kids are brought up to hustle each other and real human emotion and contact are regarded as some awful disease that must be stamped out by crash programs to develop a vaccine against it if life is to be lived to a ripe age. Even sex, that ultimate diamond, is tarnished into human commercialism and thus is turned into a crummy zircon to be worn around the ankle.” Remember the “first law of humankind…We are all each other, floating in and out of each other’s dreams and fantasies and everyday acts even the most intimate moments being crowded with dozens of others. No man is alone. If that cat only knew the half of it! I have been Hector on the Trojan barricades and will be the first woman on the moon, four months gone with a homosexual night club singer. Moonblood, moonooze. Not an artichoke here that doesn’t call me by my first name!”

Sheer need drives multiple claims of an affinity for Bosch, but here we have a book that is actually worthy of its several allusions to the infernal visionary. They may “want to obliterate your infinity,” but don’t fret, for you are “as free as your own imagination and circumstances allow you.” Refuse to be a victim “of other people’s hallucinations!” If you have sought and failed to find satori in meditation, yoga, or the controlled use of psychedelics drugs, return to this sublime penny arcade of the psychoses of western civilization, and the next time you feel inclined to fold in on yourself and spew hatred, pick up Brossard instead and learn to laugh, as Shakespeare taught you to quip, Burton to ruminate, and Proust to remember.

NOTES

- To read the story as told by Brossard, see his essay “Tentative Visits to the Cemetery: Reflections on My Beat Generation” in The Review of Contemporary Fiction; Volume 7, Number 1; Spring 1987: Chandler Brossard Number. This issue also features a number of illuminating essays on the early, steal-the-bread-from-your-dinner-table Village Brossard, an interview with the author conducted by Steven Moore in the summer of 1985, and Moore’s indispensable “Chandler Brossard: An Introduction and Checklist,” required reading for future Chandler groupies that features quite possibly the only fair criticism of Wake Up ever written. For those without a university library, the essay was reprinted in My Back Pages: Reviews and Essays (Zerogram Press, 2017) and the interview is available at https://www.dalkeyarchive.com/a-conversation-with-chandler-brossard-by-steven-moore/.

- Anatole Broyard, “A truly bad book just doesn’t happen,” Review of Wake Up. We’re Almost There, by Chandler Brossard, The New York Times Print Edition (April 4, 1971): Section BR, Page 51. https://www.nytimes.com/1971/04/04/archives/wake-up-were-almost-there-by-chandler-brossard-540-pp-new-york.html

- See “Chandler Brossard: An Introduction and Checklist.”

- “Commentary (Vituperative): The Fiction Scene” Harper’s 244 (June 1972): 106-110.

- Phil Lesh, Searching for the Sound (Little Brown, 2007): 196.

This essay was first printed in the corona\samizdat 2021 reprint of As the Wolf Howls at My Door (1992), available here: https://coronasamizdat.com/2021/04/09/as-the-wolf-howls-at-my-door-by-chandler-brossard/

This Book Kills Fascists!

Zachary Tanner

“‘I’ll tell you the fundamental difference between me and most people. While everybody else is striving to give their existence purpose, I, on the contrary,’ and he rose up in his chair, ‘am striving to give purpose existence.’”

Harry in The Double View

Ah, the tube-zonked ‘90s, localized infinity that spawned me. Has it really been twenty years? What a decade for heavy American novels! The whole schmear delights me. In no particular order: Vineland, Mason & Dixon, Underworld, The Tunnel, three of Vollmann’s Seven Dreams, Infinite Jest, Harp Song for a Radical: The Life and Times of Eugene Victor Debs, The Last Voyage of Somebody the Sailor, A Frolic of His Own, and, not to use a superlative lightly like a pinch of cream of tartar, but as the very roux with which to caramelize our now-synaptically-linked grey matter, now that we are one and the same brain, perhaps the most forgotten of its kind, As the Wolf Howls at My Door (aka Somebody’s Been Sleeping in My Bed; Somebody’s Been Eating My Porridge; Thin Air; Come Out with Your Hands Up!), the last book from the first hipster, the novel as Jungian echo chamber, as lewd bulletin board of the collective unconscious.

It has been said for seventy years and will continue to be said (unless his two forgotten, mammoth fictions happen to be read by more than the few hundred people who will somehow come across these paperback reprints) that Chandler Brossard (1922-1993) is best known today for his protobeatnik, hipster novels Who Walk in Darkness (1952) and The Bold Saboteurs (1953), which might be shelved quite nicely abreast such contemporary cult treasures as Junkie, On the Road, and Giovanni’s Room. Brossard’s career changed radically after these first two novels when the necessity of making a living required that he stoop to writing “threepenny dreadfuls,” or what are listed in his editor’s bibliography in The Scene Before You (1955) as Entertainments. After acting thusly, that is selling out, pimping the Muse, it is no surprise that his later works were pawned off as crackpot curiosities, not to mention the radicalities of style and realpolitik that will deter more than a few readers. Indeed, what little scholarship on Brossard exists has primarily concerned itself with the pre-potboiler phase. Authors don’t die; they become cultural artifacts. In 1987, several essays were collected in a slim, 196-page issue of Review of Contemporary Fiction, which is primarily a dossier on the first two novels, but also contains an unparalleled trinity of Brossard content by guest editor of the “Chandler Brossard Number,” Steven Moore: a primer on Brossard’s career from the early-50s to the late-80s, a bibliographical checklist, and an outstanding 1985 interview. One looks back at this interview, at early Brossard, at the Brossard number, at early-middle Brossard, late-middle Brossard, at mammoth Brossard, does some thinking, and finally returns to the interview:

SM: You’ve probably received less critical attention than any other significant writer of our time—

CB: Damned right.

After the “Entertainments,” Brossard spent the early 1960s writing plays and returned to serious fiction with The Double View (1960), The Wolf Leaps (written around the same time, but not published until ten years later as Did Christ Make Love? (1972)), and She Cried Out to Me (unpublished), the former two ornately-plotted tragicomedies in the spirit of the Bard with all the freedom of the French new novel, the latter yet unknown to me, the lot undoubtedly the awakening of the author’s mature use of free indirect style, often to comic, slapstick effect. Next were we treated with Chandler’s protogonzo journalism of Franco’s Spain in The Spanish Scene (1968). A few years later, Wake Up. We’re Almost There (1971), a grand Bacchanalian phantasmagoria, a wonderful book that gets at the collective experience of simultaneous sense processing (i.e. human connection) unlike any other I have ever read, appeared to virtually no recognition, and Did Christ Make Love? followed suit the next year. So began Brossard’s final twenty years of creative work, which would produce six more fictions: Dirty Books for Little Folks (1978), Raging Joys, Sublime Violations (1981), A Chimney Sweep Comes Clean (1985), Closing the Gap (1986), Postcards: Don’t You Just Wish You Were Here (1987), and finally As the Wolf Howls at My Door (1993), first published in a thick hardcover by Dalkey Archive Press the year before Brossard passed away from cancer, that edition reproduced here in facsimile, in paperback for the first time ever.

Such as when we study Henry James or William H. Gass, we have the luxury of clarifying the demarcation between the Major and Minor Psychedelicarcana of Brossard studies with the novelist’s own criticism. In his furious vituperative published in Harper’s in June 1972, we can find an artist’s statement:

True and original fiction, on the other hand, is vision, and fiction writers are visionaries. It is myth and magic, and the writers of it are magicians and shamans, mythmakers and mythologists. Their creations do not tell you what you already know. Their creations, like those of the seer or the primitive shaman, are mythical structures, including totemic systems, that integrate within one shared experience the reader and himself and the myth—in other words Man, Man with himself, his conscious and unconscious, and the world around him and the life within that world. These creative structures permit man to transcend his seeming mortal, physical limitations and soar, in and out, and yet at the same time make it unnecessary to set foot outside his room. They permit him to make those interior voyages that we have all been warned result in insanity and nonbeing and terrible punishment, without going crazy or disappearing. In fact, by taking these voyages he is sustaining and increasing his complex humanness, not diminishing it.

And as early as 1951, in response to an American literary scene plagued by campus novels, he wrote in New American Mercury:

Another thing, in those days there seemed to be a fear of sounding like another writer, of losing your individualism. This produced a diversity of styles and visions the like of which has never before been seen in our culture. Today, however, this fear seems to have been reversed; you get the impression that one mind with a thousand pencils is doing all the writing.

Maybe this is because there are simply more writers and it is harder to sound different among so many. I don’t really think this is so. I think this is simply a period of dullness, of ultra-respectability and imitation. One explanation, I venture, is that all over the country, in every college, young men and women, God help them, are being “taught” how to write the “correct” way. And a great many of the people doing this “teaching”—as if you could “teach” somebody how to be a writer—are writers who have a humdrum, unexciting technique themselves, and who can’t help teaching their students to write the way they do, whether or not the student’s own talent and material happen to gibe with this technique.

An awful lot of writing reads as though it were turned out, willy-nilly, in some “workshop” or other. (Every time I see the words “writer’s workshop,” I can’t help thinking of grammar school art class, when forty of us brats, seated at a workbench, were all trying to build the same bird house.)…The mass of today’s prose, as typified by the book under discussion (for our purposes nameless), is some strange, colorless tasteless substance, something you might call “perma-prose,” made of plastic, turned out by the roll, and quite easily converted into suspenders or belts, or used to wrap bundles with.

What does Brossard offer where most novels offer only perma-prose? What adhesive was used to bind this big black book but “the irresistible, fecund, antediluvial ooze, where tadpoles and lizards and fish were changing into birds and baboons and men, was coming into me, swallowing and reclaiming me, making me a liquescent part of the tidal wave of mankind. Other beings and their voices oozed through me: I was that transforming, ineluctable ooze of human essence.”

In “About Wake Up,” a valuable unpublished essay, Brossard describes: “I discovered my own vision, is what I am trying to say. And that my vision had its own needs, its own language and image system, which had nothing at all to do with the abstracting expertise I had picked up while snuffling under the influence of those in power.” This remained the author’s aesthetic mode for the rest of his working life, culminating in the text at hand. As in Wake Up, there are several things here which have previously been printed elsewhere. Several of the short stories, rants, and naughty fables here first appeared in readily-available literary journals or in limited runs such as Dirty Books and Postcards, though these books are still worth individual pursuit for such absent treasures as “Jack and the Beanstalk: A Hustler’s Progress,” “Hansel and Gretel: Why Should Sleeping Dogs Be Permitted to Go On Lying,” “Rumplestiltskin: Don’t Fuck Around with Dwarfs,” and a third Little Red Riding Hood tale subtitled “A Novice Policeman’s Original Oral Report to the Chief of Security and the Director of Special Medical Inquiries.” The only Postcard reproduced in its entirety is Letting Bygones Be Bygones, Oregon, but the postcard vignette structure is adapted freely and enigmatically. The pragmatic collector can find both of these and more in the posthumous edition, Over the Rainbow? Hardly: Collected Short Seizures (2005).

What the totality amounts to is an “autarkic” classic of vernacular lyricism like Omensetter’s Luck or The Dick Gibson Show, an insane labyrinth of metafictional asides used as an enjambment method in a vast circus of erotic tales reminiscent of Wally Wood’s Malice in Wonderland and Far Out Fables, peppered with disembodied voices, obscene intrusions, word salad, exorcised consciousness, the author’s former work, rabid lunges at the puppet-masters of American foreign policy, and, most spectacularly, several double-identity soliloquies à la The Double View, all of it together staging the documentary depravity of Malaparte through a Playboy lens, the entire production directed by a madcap obsessed with such oblique fictions as Hind’s Kidnap and V., and finally screened by a projectionist who has “gone bananas.” In his essay, “The Abuses of Enchantment,” William Levy pegs Dirty Books with an onion roll from forty yards as a Menippean satire, which, in relation to the eventual work within which Smut for Small Fry was subsumed, is not only fair but worth careful consideration. Certain modern readers will be made uncomfortable by the slurs and hate-speech thrown about so carelessly in this book by such characters as Truman, Nixon, and Ishmael, but we must remember that these are not the symbols of the author, but of the Empire. As a queer, I am not so offended by the use of “faggot” and “cocksucker” in a book where I am also gifted a veritably European amount of full-frontal male nudity and “a dialectical analysis of the perpetuation by the mass media of the mythology of black cock.” If one can look past the scatological humor commonly endemic to great English novels such as Gravity’s Rainbow, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, and JR, perhaps, like me, you’ll find evocations of Chaucer, Varro, and Petronius in this authentic hunk of homegrown, cornfed anti-Americanism, a sprawling work of the magnitude of Flaubert’s Bouvard et Pécuchet or Sergei Eisenstein’s ¡Que viva México!

Ultimately, As the Wolf Howls at My Door asks the sort of big questions only fiction can ask, such as: “What was Julius Caesar supposed to do or say when he woke up that particular morning, turned his wife Calpurnia over for a better shot of her ass, then looked up and saw all those fucking elephants pouring out of the Alps with Hannibal in the lead? What was Big C. supposed to do? Call up the director of the Zurich Zoo and say, Kurt, I think there’s been a bad breakout, fella? Grab his autographed copy of The Decline of the Roman Empire to see if the whole thing wasn’t some kind of typo? Goddamn drunken printers. Or simply go right on fucking his wife up her ass? Try putting yourself in his toga and see how smart you feel. It’s about time you Monday-morning quarterbacks got straightened out and called onto the mattress.”

Here is a book for readers kindred with our buxom Little Red: “She could have taken the shortcut, a well-ordered path cut by the village council and used by the utilitarian villagers who had no inclination to mess around, but she preferred the longer, more arduous way that took her through the unkempt, raunchy parts of the forest where one’s imagination could get a little nourishment. Odd and slinky animals abounded there, as did trolls, centaurs, gremlins, thieves, gypsies, mushrooms, marijuana, and brazen birds with long wings and big mouths.”

Behold the last great work of the patron saint of autodidacts, anathema to North American anti-intellectualism, Chandler Brossard’s As the Wolf Howls at My Door.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This essay was first printed in the corona\samizdat 2020 reprint of The Wolf Leaps (1973, aka Did Christ Make Love?), available here:

https://coronasamizdat.com/2021/08/29/the-wolf-leaps/Sure, Christ Fucked, but Was He on Top?

Zachary Tanner

I first read Did Christ Make Love? in February of 2021 in the middle of a six-month study of Brossard that I was undertaking while writing my introductions to the corona\samizdat reprints of Brossard’s two mammoth novels, Wake Up. We’re Almost There and As the Wolf Howls at My Door. In light of my scholarly endeavor, I bought all the Brossard I could get my hands on, my copy of Did Christ Make Love? (1973) a signed HCDJ 1st ED which I purchased for $59.65, which was the only copy I could find on the internet. (As I write this introduction, I can find absolutely no copies online.) I read it over the course of an afternoon, most likely over three or four tequila-ice-limes, for I was drinking heavily while on antidepressants at the time, which I would not mention but to note that the liberated imagination of Chandler Brossard’s fiction was essential to my recovery.

At this point, I was about nine months into my daily ongoing conversation with Rick Harsch, who had introduced me to Brossard but a few months before when he asked me to introduce his paperback edition of Wake Up. Like I said, I read this book in one inebriated sitting, not counting the trips from my shed to the kitchen and back, and when I put it down, I likely sent a rough snapshot of my blurry, sweating mason jar next to the book with something along the lines of “not true what they say, Brossard can write a plot, and better than the rest, as well as the Bard himself.” I gushed about the book until it was time to move on with my day, thinking little of it but of my next drink, which would taste sweeter thanks to the afterglow of reading a novel, but within the hour, Rick had written the Estate:

The person working on the introduction to Wolf has told me that we should publish Did Christ Make Love. Can I have your permission?

Soon after, Rick wrote Steven Moore (who had been providing guest editorial directions on behalf of his friend Chandler for us since we reprinted Raging Joys, Sublime Violations) about our edition of this book and he said:

“That’s great news about Did Christ Make Love?, though I hope you will use Bross-ard’s original and preferred title, The Wolf Leaps.”

He also passed along a copy of a Foreword he wrote “for an edition that was supposed to come out 20 years ago but didn’t,” which has remained unpublished until now, in which he refers to The Wolf Leaps as “the least known of Brossard’s novels, the scarcest on the used-book market, and the only one not to have been reprinted as a paperback in his lifetime.”

Why is that the case? Beyond the fact that all of Brossard’s work was and has remained neglected? Does it have to do with “the only crime worse than marrying your mother and murdering your father?” Or because it’s a novel in which white merry wives of priests invite sapphic black parishioners up to their apartment under the guise of a half-baked pretense, and, as they are tempting them into hardly verbally consensual sex-massages, have the caucacity to say something like

“And just think how nice it must be, Cynthia, how almost unnaturally blissful, not to be wakened in the middle of the night by the screams of people being mugged or raped or beaten to death in a race riot, Mm, heaven.”

What is the crime worse than Oedipus’s? Why, the star-crossed trysting of a white priest and a black hustler.

And yes, star-crossed, again, as I drunken-ly tried to convey to Rick with my choice of the word Bard, for it is the dramatism of this novel that makes it a novel novel. In his note “To the Reader” in Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, Harold Bloom writes:

In Shakespeare, characters develop rather than unfold, and they develop because they overhear themselves talking, whether to themselves or to others. Self-overhearing is their royal road to individuation, and no other writer, before or since Shakespeare, has accomplished so well the virtual miracle of creating utterly different yet self-consistent voices for his more than one hundred major characters and many hundreds of highly distinctive minor personages.

What is the crux in this crucifix of a novel but the moment that Rojas later recalls as Harrison giving “the distinct impression he was carrying on a most impassioned and urgent interior dialogue with his two warring selves.”

When on the pulpit, our white Jesus has his epiphany amidst some of the most sublime writing in the entire novel:

“I wonder how many of us really know what it means to believe, what the vast implications are of believing. I suspect that many of us either have the wrong understanding of this, or at least are not as actually involved in it as we should be. For example, what does it mean when we say that we believe in another person? Does this mean merely that we know this person won’t lie to us, or try to steal our money? That we are sure this person will be nice to us? If that is all we mean, then we might as well give up. Because belief in another human being means infinitely more than that. It means that we accept his infinite capacities for becoming an extraordinary person, for rising above the limitations we see before us. Belief, real belief, between two people is a kind of magic. With this God-given magic there is nothing they cannot do, nothing they cannot feel, nothing they cannot create. A human paradise comes into existence, a realm of feeling and liberty, without which we are nothing but self-deluded sleepwalkers.”

What more fertile consciousness moment for Shakespearean self-overhearing than the sermonizer on the mount? The beauty of this book is self-evident.

My initial enthusiasm for the jouissance of The Wolf Leaps came from the place in my heart that cherishes William T. Vollmann’s O’Farrell Street hagiographies. And from a narratological standpoint, Did Christ Make Love? (for as such did I know it) had it all: striking monologue-based, flashback-driven non-linearity condensed into a zip-bang tragicomic structure, fluid peripeteia and a delayed anagnorisis, the libertine duplicity of a cast of characters each thinking of other lovers than the ones they are obligated to love, with several dying from their taboo affections while we see directly inside each of their idiosyncratic thoughtspeech peregrinations according to the narrator’s whim, and ultimately, by it all, the soft, full frontallove that is so uncommon in the 21st century, of which wrote Ovid, Petronius, and Apuleius, whose timeless eroticism Brossard as Bard seemed to adopt under the guise of modernism, i.e. the quoted monologue. As with The Double View, The Wolf Leaps represented a wild diversion from early Brossard that paved the way for later Brossard while they both remained distinct from the rest for their mature flirtation with free indirect style and clever plotting. As Dorrit Cohn writes in Transparent Minds: Narrative Modes for Presenting Consciousness:

A monologuist in a third-person context is not the uniquely dominant voice in the text we read. He is always more or less subordinated to the narrator, and our evaluation of what he says to himself remains tied to the perspective (neutral or opiniated, friendly or hostile, empathic or ironic) into which the narrator places him for us.

I doubt more need be said to bait some wayfaring scholar out there to unpack this thing for us once and for all, but until such time please take a long look at the following two ephemera I have created (with obvious limitations in the approximations of the latter as such considerations as characters’ ages and therefore the sequence of their individual adolescent escapades are unknowable to me; I have done the best I can with what I have in order to make this unique novel’s idiosyncratic complexity evident at a glance):

Dramatis Personae

Harrison—episcopal priest

Monique—hustler

Dancer—her pimp

Rojas—concerned parishioner

Elaine—Rojas’s betrothed

Leslie—wife of Harrison

Cynthia—lover of wife of Harrison

Alba—waitress-turned-hustler (thanks to Dancer)

Alba’s Boyfriend

FABULA SEQUENCE:

GG, V, Y, R, H, E, A, B, C, D, F, G, I, J, L, Q, CC, M, N, O, U, P, BB, S, T, W, X, FF, Z, AA, DD, EE, HH, II, JJ

SYUZHET SEQUENCE:

A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z, AA, BB, CC, DD, EE, FF, GG, HH, II, JJ