This essay was first printed in the corona\samizdat 2021 reprint of Love’s Cross-Currents (1905), available here:

Joli ménage!

by Zachary Tanner

“The world of Swinburne does not depend upon some other world which it simulates; it has the necessary completeness and self-sufficiency for justification and permanence.”

-T. S. Eliot1

Need one be a sex-positive, 21st-century “esoteric of the Garden” into impact play who has read their Joyce and de Sade to relish Swinburne’s subtle, iconoclast novels? Maybe it takes one of us to savor the author’s cryptic treatments of forbidden eros, but certainly we’re not the only reader demographic capable of appreciating the vernacular prose-poetry of this Victorian ode to the Epistolary Novel, and so, let the people their Swinburne, for as the author once wrote of the “Arch-Professor of the Ithyphallic Science,“ I “would give anything to have, by way of study, six or seven other opinions as genuine and frank as mine shall be.”2

What turned me on to Swinburne? No doubt coming across some striking legend such as the one I came across in Richard Church’s introduction to my Everyman’s Library edition of Swinburne: Poems & Prose:

“Swinburne the tadpole-scholar was a quiet member of his aristocratic family, aloof and retiring. But enrage him with drink, or poetry, and he would become poisoned with all possible forms of mental and emotional perversity, calling upon the ghost of the Marquis de Sade to initiate his imagination into the more exquisite forms of sensual indulgence, or evoking the lamian beauty of some Renaissance strumpet so that he might boast to his Victorian public of fictitious dallyings with her.”3

On the threshold of Swinburne studies, one finds a basket of nasty letters about the author’s eccentric personality, the mass of uninspired tweed-types loving to hate as it does the marvel of such functional substance abusers as William S. Burroughs or Rainer Werner Fassbinder—in Algernon the makings of a genderfluid movie starlet who lived out life’s best years before the moving image was around to lend a longing luster to the monotonous ordeal of one’s despair. What I’m getting at is the debased genius of Mozart that Hollywood imagines would have so disgusted Salieri. What we find is the Blakean primacy of sensual experience lucidly deranged in a manner reminiscent of Rimbaud in the forgotten novels of a poet contemporary of Dickens, Dumas, Balzac, et al. Any reader with an affinity for the biographies of literary eccentrics will find a doozy in Swinburne and may turn to any of a number by Lafourcade, Fuller, Thomas, and Henderson, sparing Gosse only for its historical importance, for, as Beetz writes in Algernon Charles Swinburne: A Bibliography of Secondary Works: “…Gosse relied heavily on unreliable sources and possibly apocryphal anecdotes for his bio.”4

Originally published serially as A Year’s Letters in The Tatler in 1877 under the pseudonym “Mrs. Horace Manners” (fifteen years after it was written), Love’s Cross-Currents was finally published in book form in 1905 after the death of the author’s parents. May they not roll in their graves to be dug up again for our purposes here.

But to read Love’s Cross-Currents one hundred and sixty years after it was begun, more than a century still since it was finished, need we know—to enjoy this elegant fiction—that it was inspired by several very real Life Events concerning Swinburne and his cousin Mary Gordon, to whom he read sections of this novel before her marriage? Need we know of Adah Isaacs Menken to appreciate Miss Lenora Harley of Lesbia Brandon? What of the hat stomping episode? What of Swinburne adoring and corresponding with Baudelaire before the English speaking world knew he was cool? Need we recognize a Caroline lyric as such to cry over the verse? Well?

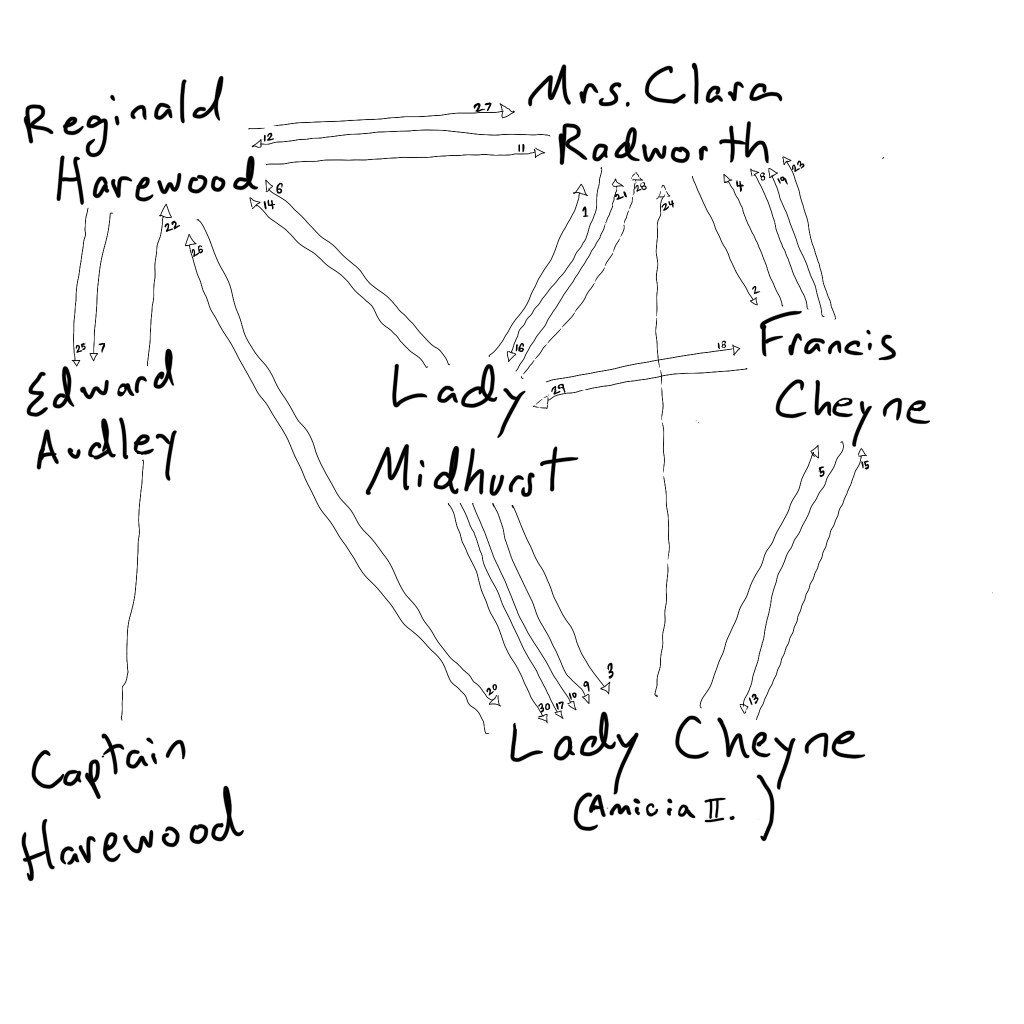

I turned to Goodreads, in search of contemp-orary opinions, finding only a single text review from user Steven, who writes, “Anyone who gets through the book does so only by dint of drawing up a family tree to keep straight its three sets of cousins.” I don’t know if I necessarily agree. I charted out the birthdates in the Prologue on the flyleaf, but didn’t bother with a family tree until my second reading, and I don’t think Love’s Cross-Currents is any more difficult to follow than the familial contortions of Austen, Faulkner, Nabokov, or Tolstoy. In fact, I believe that it reads so well and in such a surprising, revelatory way that I hesitate to spoil the story in the introduction with any kind of analytical summary, beyond reiterating what Swinburne wrote of the novel in an early Spring letter to Rosetti in 1866: “This book stands or falls by Lady Midhurst; if she gives satisfaction, it must be all right; if not, chaos is come again.” Any reader who requires such a summary before reading a suspenseful plot can turn to the Falcon Press edition of Lesbia Brandon and Randolph Hughes’s Commentary within, where is given from pages 285 to 288 “a rapid account of the family, in so far as it is necessary to an intelligence of the situation as a whole.”

What need we know beyond the fact that betwixt this quasi-incestuous love quadrangle (it only counts if it’s your first cousin), a broken-hearted dreamer will write to the unrequitable object of passion: I do not think you can mean to break with all our hopes and recollections and change the whole look of life for me. (p.132) What do you do when the person you love has resolved to have done with you? Well? “Of course the boy talks as if the old tender terms between them had been broken off for centuries, and their eyes were now meeting across a bottomless pit of change. I shall not say another word on the matter: all is as straight and right as it need be, though I know that only last month he was writing her the most insane letters.” (p.263)

“Le dénoûment c’est qu’il n’y a pas de dénoûment.” (p.267)

But I would sell the reader short should I not make some sort of tangible scholarly analysis of this book as Epistolary Novel. Randolph Hughes asserted that the book’s only artistic deficiency was that the seaside mid-point did not grow out of the initial conditions of the story.

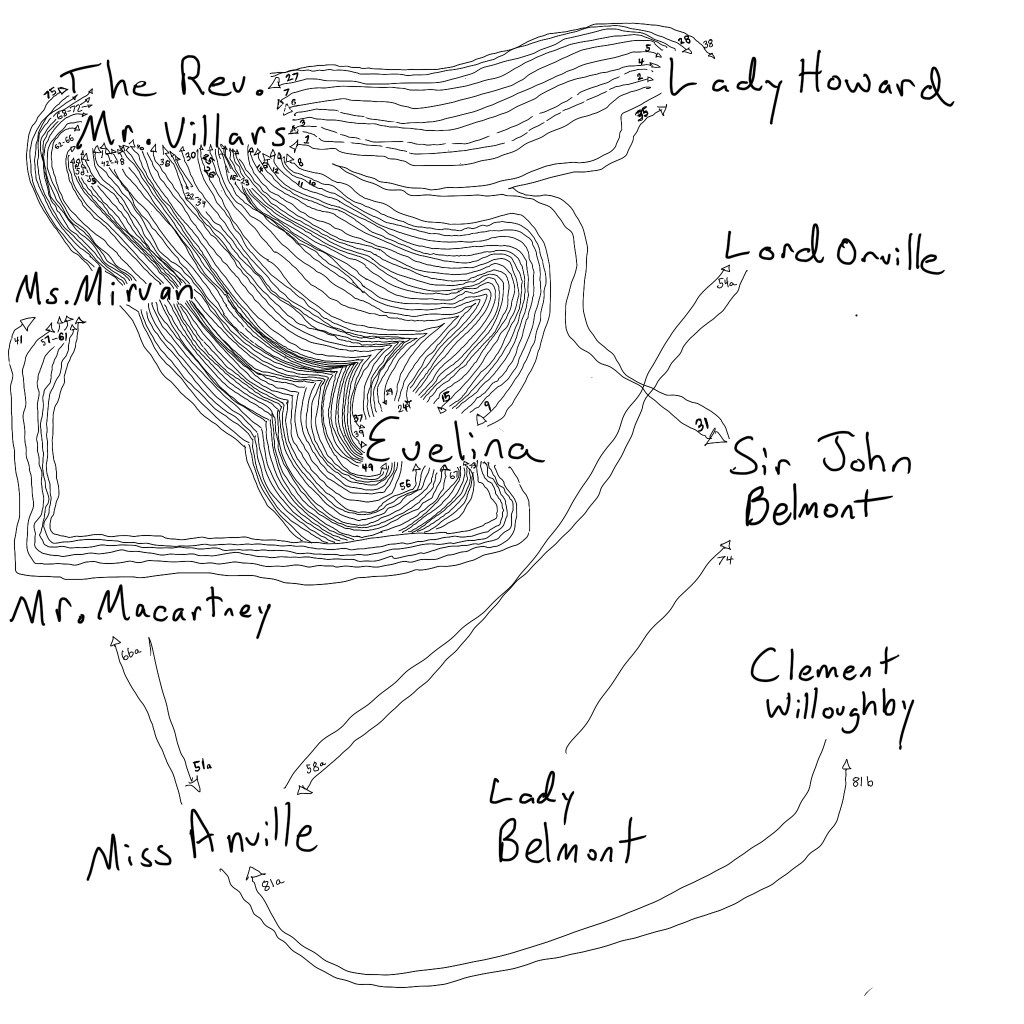

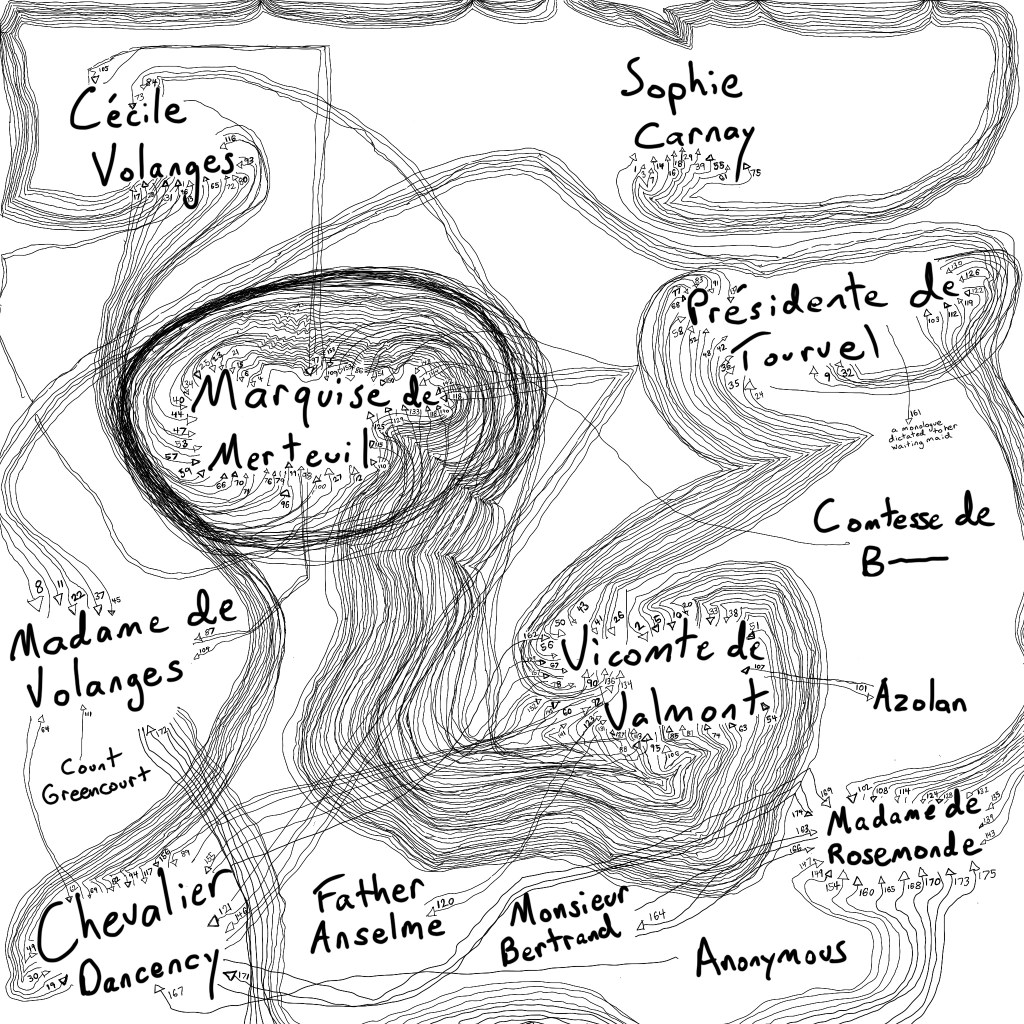

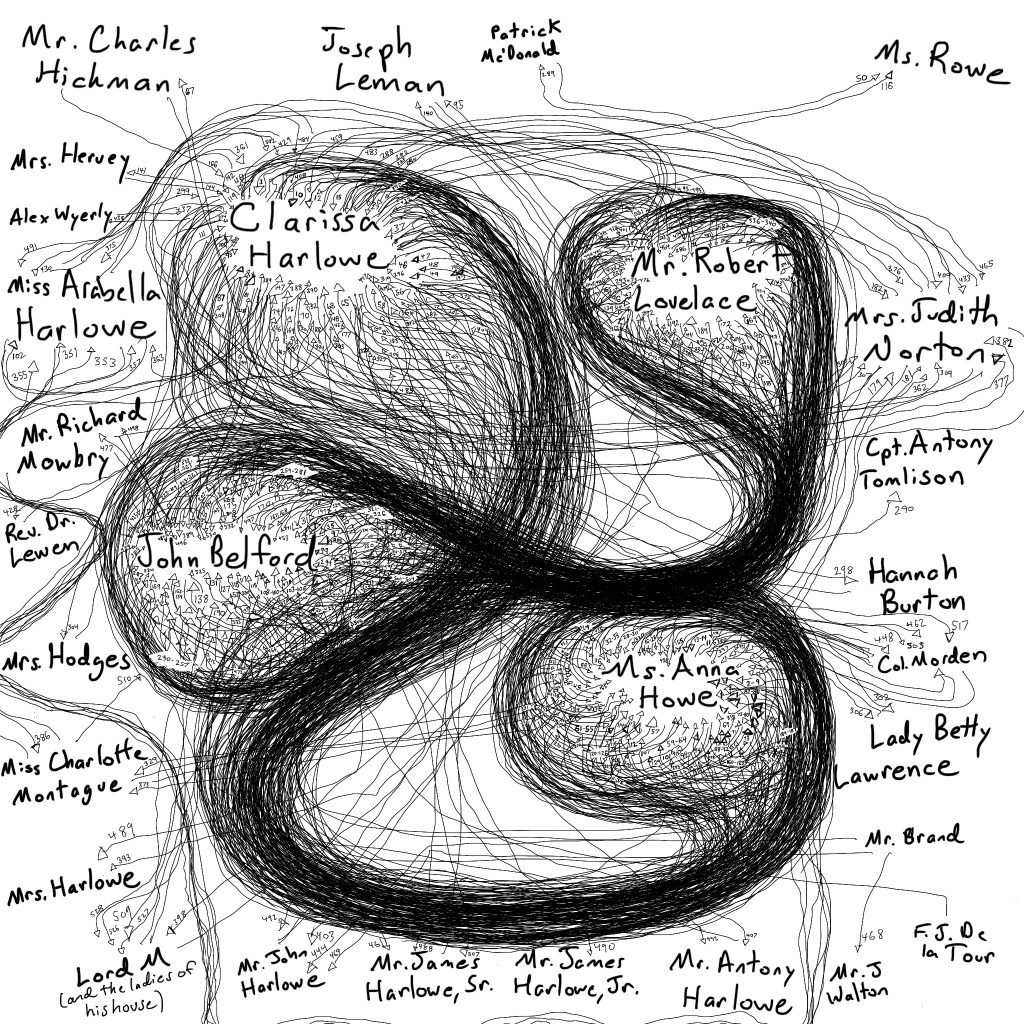

I, however, fault Swinburne’s artistry for not making any such use of the seemingly infinite variation of metafictional conditions that might exist in a text of this sort. Though in its own unique way, it rewards readers familiar with Laclos, Richardson, and Crébillon Fils, it makes little use of such liberated effects in those other novels as letters recopied, resequenced, enclosed within other letters, continued, annexed to the former, dictated by Valmont, written by a waiting maid, now sent along with copies of letters to uncles and their responses, delivered same-day, written at daybreak or nightfall, within an Ivy Summer-house, interrupted by nervous mothers, for each letter in these classic epistolary novels, a new trick, in them vast rewards for any fan of postmodern metafictions, but in Love’s Cross-Currents, never do we find this hypertextual delight that most other novels of this sort have to offer. It is not the sort of story where a character continues a letter, having sat up late to finish and seal in readiness a letter in response to the above, only to be interrupted at dawn by the arrival of thy second fellow which infinitely disturbed us all. But it could have been.

A simple visual analysis of four novels should suffice to exhibit something of Swinburne’s perplexing non-comformity. That with such a simple schematic and so few letters, a story of the same depth as these others is successfully told is something I find quite striking, whereby somehow the poet’s deficiencies as a novelist boost the work. It is also telling of the claustrophobic nature of this study of concurrent familial temperaments.

Behold the Enchantments of the Genre:

Evelina(1778)

by Frances Burney

84 Letters from March to October

Les liaisons dangereuses (1782)

by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos

175 Letters from August to January

Clarissa; or, The History of a Young Lady: Comprehending the Most Important Concerns of Private Life. And Particularly Shewing, the Distresses that May Attend the Misconduct Both of Parents and Children, In Relation to Marriage (1748)

by Samuel Richardson

537 Letters from January to December

Love’s Cross-Currents (1905)

by Algernon Charles Swinburne

30 Letters from January to February following

If it is perhaps insufficient in the very form in which it’s written, what makes this a worthwhile read is that “the genuine stamp of a sincere and single mind was visible throughout; which was no small comfort.” (p.11) “To be face to face with such a dead and buried bit of life as that was so quaint that stranger things even would have fallen flat after it.“(p. 260)

The striking whole amounts to something that models quite closely the experiences I’ve had of sending and receiving messages in this instantaneous, globalized world, well-wrought art offering as it does timeless relief beyond generational boundaries, creating an empathic connection between the living and the dead. What a marvel like a shell upon a beach is this!

NOTES:

1T.S. Eliot, The Sacred Wood (London: Methuen & Co., Ltd., 1920), “Swinburne as Poet.”

2To Richard Monckton Milness – August 18, 1862, in Volume 1 of Lang’s The Swinburne Letters, p. 53-59. He continues playfully: “At first, I quite expected to add another to the gifted author’s list of victims; I really thought I must have died or split open or choked with laughing. I never laughed so much in my life: I couldn’t have stopped to save the said life. I went from text to illustrations and back again, till I literally doubled up and fell down with laughter. I regret to add that all the friends to whom I have lent or shown the book were affected in just the same way.” But what I find especially interesting is the way that Swinburne is able to subvert even the Arch Pariah of Subversion: “But in Justine there seems to me throughout to be one radical mistake rotting and undermining the whole structure of the book. De Sade is like a Hindoo mythologist; he takes bulk and number for greatness…I boast not of myself; but I do say that a schoolboy, set to write on his own stock of experience, and having a real gust and appetite for the subject in him, may make and has made more of a sharp short school flogging of two or three dozen cuts than you of your enormous interminable afflictions; more of the simple common birch rod and daily whipping-block than you of your loaded iron whips and elaborately ingenious racks and horses.”

3p. xi.

4p. v.

This essay was first printed in the corona\samizdat 2021 reprint of Lesbia Brandon (unfinished), available here:

What Was Electra Like, Do You Think?

By Zachary Tanner

“The absurd prose style of his later period requires no comment beyond Edward Thomas’s observation that if De Quincey and Dr. Johnson had “collaborated in imitating Lyly they must have produced Swinburne’s prose.”

-C. Y. Lang1

When The Falcon Press posthumously published Lesbia Brandon in 1952, the novel was sandwiched between an irate foreword and hundreds of pages of commentary from Randolph Hughes2 that vacillate between elegant analysis of Swinburne’s two English-language novels, imprecise attempts to critically situate Swinburne in the canon of Major Novelists while rejecting the traditional categorization of the novel (“I venture to claim that I have at least shown that the most generally accepted canon of the novel, that formulated by Stevenson, Hardy and Arnold Bennett, for instance, and by the most influential French critics, and regarded by them as the one and only ideal, a supreme form after which all good novelistic work must aspire, has not universal validity, and is not the only nor necessarily the highest norm for the evaluation of success.”)3, exhaustively-researched finger-point-ing at the shady figures and dealers who have clung to, hindered, and obfuscated the Work of Swinburne, most singularly Algernon’s “friend” and solicitor, Theodore Watts-Dunton (of whom Hughes writes: “There are at least two crimes from which Watts-Dunton can never be absolved: the sale of his dead friend’s manuscripts to the unlettered pedlar and the forger Wise, and the frustration of a work that had in it the makings of a masterpiece.”), and finally a section of scholarly justification on the Text as constituted and compiled from the typeset drafts and manuscripts forty-three years after the death of the author. “The general reader will no doubt not bother about this last section; but scholars will expect it in the case of a new book of this sort of which the sources of the text present a large number of problems; and it is essential in order to justify my own arrangement of the text, which differs considerably from that of Wise, and also from that of the galley-proofs.”4

Though riddled with the errors, inconsist-encies, and misprints pointed out in C. Y. Lang’s letter to the Times Literary Supplement,5 the Hughes edition was the same chapter arrangement and text to appear in a slightly corrected form in The Novels of A. C. Swinburne (1962). The corona\samizdat edition has been based off of the Hughes, altered only by basic copy editing for grammar and sense to correct obvious misprints in the original.

Hughes’s telling of the missing chapters of Lesbia Brandon is where I found the sad, pleading letter from Swinburne that has been reproduced on the back of this book, and this section of the Commentary makes wonderful reading for those with the bitter taste for Victorian-era gossip. Though Hughes’s bombastic rhetoric at times is not but outright mud-slinging, there is much of import to be found, and the whole amounts to one of the most anally ambitious novel studies I’ve had the pleasure of reading, though as Lang has shown, for all his diligence it may not be infallible, and in no phoneme is it unbiased.

Hughes’s foreword, though, is a great essay on Swinburne (one wonders that it couldn’t have been enough to settle his hard feelings), and the entire edition represents a monumental event in the history of publishing, Hughes’s decade of work to restore the unpublished prose and naughty poems of Swinburne. Therein we will learn from Hughes that Lesbia Brandon, however fantastic, is a false title that “has acquired a standing through its present in Wise’s Catalogues, and has been used of the work whenever the latter was mentioned in all publications relating to Swinburne printed in the last forty years or so, it has seemed best not to seek to alter it.”6 If I could recommend only two essays for the general reader on the fiction of Swinburne, I’d recomm-end the Hughes foreword and Edmund Wilson’s introduction to The Novels of A. C. Swinburne, aka “Swinburne of Capheaton and Eton”7, 67 pages of buried criticism readily accessible in virtually any English-language university library offering clarity to the story of this story, and its (lack of) reception for a century and a half and then some.

Scholarship of this sort becomes very important in understanding a poet-novelist like Swinburne, for I know no one by face and name alive today who would be able to readILLA RUDEM CURSA PRIMA INTUIT AMPHI-TRITEN and immediately peg the reference to Catullus, personal poet such as Swinburne, perhaps best known for a series of poems about a lover named Lesbia—eureka!—which brought me to the computer, where I found a faithful reproduction of the image by Weguelin of Lesbia from Catullus, used in this edition as a frontispiece, which seemed appropriate because it was another telling of Catullus painted in the year after Swinburne had portions of this novel typeset, and I also think it goes pretty well with the portrait of Ophelia on the cover by Burthe, which is appropriate in its own right because Swinburne mentions honest Iago in both of his novels. To the post-modern reader whose cyborg scholarship of text and image in the library and on the internet often offers such vertiginously labyrinthian synchronicities, Swinburne’s poly-lingual novels and letters are more accessible than ever, for what reason, these days, has one to fear for Hungarian in Gaddis when we can understand the Latin in Sterne with a wi-fi connection? The corona\samizdat reprint rep-resents the first time this novel will appear simply bound in an accessible pocket paperback form, to stand on its own, without the dressings and euphemisms of biased scholarship holding its hand, to let readers decide for themselves whether the allusions are worth the scholarship to understand them after all this time.

On the other hand, I, for one, have no trouble reading this book simply for my pleasure. We have in hand an unfinished “masterpiece” such as The Pale King or Jean Santeuil. Let us not confuse these sketches, nor Lesbia Brandon, with such Unfinished Masterpieces as À la recherche du temps perdu or Bouvard et Pécuchet. However, “There is always something attractive in failure after a time, as strong as there is for the minute in success.” (p.126)

Every time I resurface from a dip in this novel, I feel like Herbert at the waves: “His face trembled and changed, his eyelids tingled, his limbs yearned all over: the colours and savours of the sea seemed to pass in at his eyes and mouth; all his nerves desired the divine touch of it, all his soul saluted it through the senses.” (p.10) For good fiction gives me the satisfaction our debutante Herbert seeks in the world: “To retain his own eyes and see also with another man’s—to retain his own sense and acquire another man’s…” (p.36)

Swinburne began writing Lesbia Brandon in the 1860s, and in 1877, the same year his other novel Love’s Cross-Currents originally appeared in The Tatler as A Year’s Letters by “Mrs. Horace Manners,” had several chapters set into type. A quick glance at my ALSO BY ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE printed on the back of the book’s front flyleaf is a wonderful place to appreciate at a glance how many incredible, whole pieces of art Swinburne created during his long tenure as novelist manqué, but for the fan it is worthwhile to visit three readily available Chronologies: Erhsam’s in Bibliographies of Twelve Victorian Authors, Welby’s in A Study of Swinburne, and Nicolson’s in Swinburne.

Though Lesbia Brandon was never finished, what remains between covers certainly contains a spark of what Swinburne so admired in the Brontë sisters: “a quality as hard to define as impossible to mistake; even the static and dynamic terms of definition so freely and scientifically misused in the latest school of feminine romance would scarcely help us much towards an adequate apprehension or expression of it. But its absence or its presence is or should be anywhere and always recognizable at a glance, whether dynamic or merely static, of a skilful or unskilful eye to discern the style from the diastole of human companionship—or even inhuman jargon. The crudest as the most refined pedantry of semi-science, tricked out at second hand in the freshest or the stalest phrases of archaic school-men or neologic lecturers that may be swept up from the dustiest boards or picked up under the daintiest platforms irradiated or obfuscated by new lamps or old, will avail nothing to guide any possible seeker on the path towards an exploration by physical analysis or metaphysical synthesis of the source of the process, the fountain or the channel or the issue, of this subtle and infallible force of nature—the progress from the root into the fruit of this direct creative instinct.”8

Contemporary readers educated in North American Creative Writing Workshops or reading this introduction at a pay-by-the-week retreat may find themselves cringing at double adjectives, rhymed prose, and, heaven forbid, several descriptions of eyes and faces, but in the most beautiful way I see Lesbia Brandon like Lady Midhurst sees Nature: “I do think, if she had her own way, would grow nothing but turnips; only the force that fights her, for which we have no name, now and then revolts; and the dull soil here and there rebels into a rose.” (p.200)

Let scholars seek out scholarly editions. For the rest of us, we sensualists, the readers who read to live the lives of others and develop a complex taste for diversity, let’s drop a needle on Schoolboys in Disgrace and take this Lesbia–Brandon-without-training-wheels in hand as we roam the Earth in search of the vastness of the sea to be found in another’s eyes by the power of the heart.

Vivamus, mea Lesbia, atque amemus.

NOTES

1Page xvii of Lang’s Introduction to Volume 1 of The Swinburne Letters, which covers 1854-1869. “About two thousand letters will be printed in these volumes. The manuscripts have been assembled from nearly three dozen libraries and about fifty private collections, and in addition I have reprinted letters, of which the holographs have not been found, from several dozen books and periodicals.”

2Algernon Charles Swinburne, Lesbia Brandon (The Falcon Press, 1952), from which I have pulled for the sake of these notes several portions of the manuscript that were deleted, to retain some sense of the manuscript as Swinburne envisioned it as it may have been handed down had it been published in the 1870s (around the time author had the majority of the manuscript set into type) by the London pornographer Hotten under a pseudonym abreast such classics as Flagellation and the Flagellants, a History of the Rod in all Countries, Lady Bumtickler’s Revel, or A Treatise of the Use of Flogging in Venereal Affairs. Here are a few of my favorites:

i)“When after some months he took hold of his courage with both hands, heaved his heart into his mouth and begged [with moist eyes and fiery cheeks that he might not be] [hoisted or held down by a servant, promising: : hoist across the whipping-block by a servant, promising] to be no longer hoisted, promising to keep quiet and take his due allowance of cuts without wincing, Denham acceded with a sharp laugh, and thus [thenceforth] chair or sofa [became substituted for the wooden horse] served the purpose of a school block, and every flogging.”

ii)“The sting was doubled or trebled; and he was not release still blood had been drawn from his wet skin, soaked as it was in salt at every pore: and came home at once red and white, drenched and dry. Nothing in his life had ever hurt him so much as these.”

iii)“Feverish hands, he knew, would deal but inadequate strokes: and he was on all accounts inclined to give Herbert something to remember for life.”

iv)“A few words or warning menace and sharp reproach were intermixed between the stripes; and after each pause of the kind a long switching cut was laid on which left deeper marks on the boy’s smooth skin [which made the room echo, answering upon].”

v)“Noticed the print of his knees on the couch, the tumbled cushion, and among other significant minor indications sundry broken twigs of birch lying about, bruised buds and frayed fragments of a very sufficient stout rod. That well-worn implement, no longer fresh and supple, with tough knots and expanding sprays, but ragged, unsightly, deformed and used up, lay across a chair close at hand, not without [specks] marks of blood [about] on it.”

vi)“This sentence was sportively enforced by a sharp stroke with a flat hand which made the boy cry out and catch his breath: the secret pinch that followed brought the tears full into his eyes, and his teeth pressed his underlip hard: these caresses had literally enough touched a tender part.”

vii)“He had found out by means of a fresh blow with the hand, which brought such exquisite pain into Herbert’s face as could not be mistaken or controlled: the cheeks were contracted and the whole body quivered.”

3Ibid, p. xxvii.

4Ibid, p. iii.

5See essay by Edmund Wilson mentioned shortly.

6Falcon Press edition, p. xxviii.

7This introduction originally appeared in The New Yorker in somewhat different form in 1962.

8Algernon Charles Swinburne, The Complete Works of Algernon Charles Swinburne (New York: Russel & Russel, 1968), “A Note on Charlotte Bronte,” p. 4-5. This edition is a reissue of the 1925 Bonchurch Edition of The Complete Works of Algernon Charles Swinburne.

6Falcon Press edition, p. xxviii.

7This introduction originally appeared in The New Yorker in somewhat different form in 1962.

8Algernon Charles Swinburne, The Complete Works of Algernon Charles Swinburne (New York: Russel & Russel, 1968), “A Note on Charlotte Bronte,” p. 4-5. This edition is a reissue of the 1925 Bonchurch Edition of The Complete Works of Algernon Charles Swinburne.